Minsk-ing Through Time

I arrived at the Belarusian immigration office, a grim Soviet-era building that looked like it had been stuck in a time warp since the 1970s, ready for what I assumed would be a thorough, no-nonsense interrogation. In preparation, I had purged my phone of anything that might have raised a suspicious eyebrow and even learnt how to say, “You’re looking very snappy in your green uniform today,” in Belarusian—just in case a bit of flattery could smooth the way. The guards certainly looked snappy, wearing towering, high-brimmed hats that seemed designed not only to keep the winter snow from settling on their faces but also to intimidate. Despite their appearance, I’m fairly certain most of them were still in the grip of sleep at 6 a.m., as my questioning consisted of little more than the usual, tedious border guard queries. Less than fifteen minutes later, I was stamped and waved through, and I let out a breath so deep I think it might have been heard back in Vilnius.

Once the border had slipped from the coach’s rearview mirrors, I was left to ponder what exactly one does for a day in Minsk—something I probably should have given more thought to beforehand. With no internet, no guidebook, and only an offline map of the city to guide me, I was left to rely on nothing but instinct and my astonishing nose to locate the capital’s interesting locations. The idea of exploring the old-fashioned way was actually quite liberating—at least in theory—so long as I didn’t accidentally stumble upon a military base or, worse, find myself snapping a selfie outside Lukashenko’s living room.

Three hours later, still groggy myself, I stepped off the coach and spotted a tourist map of Minsk at the bus station—an unexpected and welcome find. After a quick glance over my shoulder, I set off towards what looked like a grand plaza. Along the way, I passed what must be the most photographed KFC in the world, sitting beneath a massive socialist sculpture, and a group of filmmakers shooting what appeared to be Top Gear Belarus. When I reached the plaza, I wasn’t disappointed. The grandeur of the square and the Palace of the Republic at its centre was impressive, flanked by national flags and posters advertising performances by the Belarusian Elvis (not to be confused with the magnificent Latvian Elvis). It felt like stepping into the heart of the most Soviet remaining spot on earth.

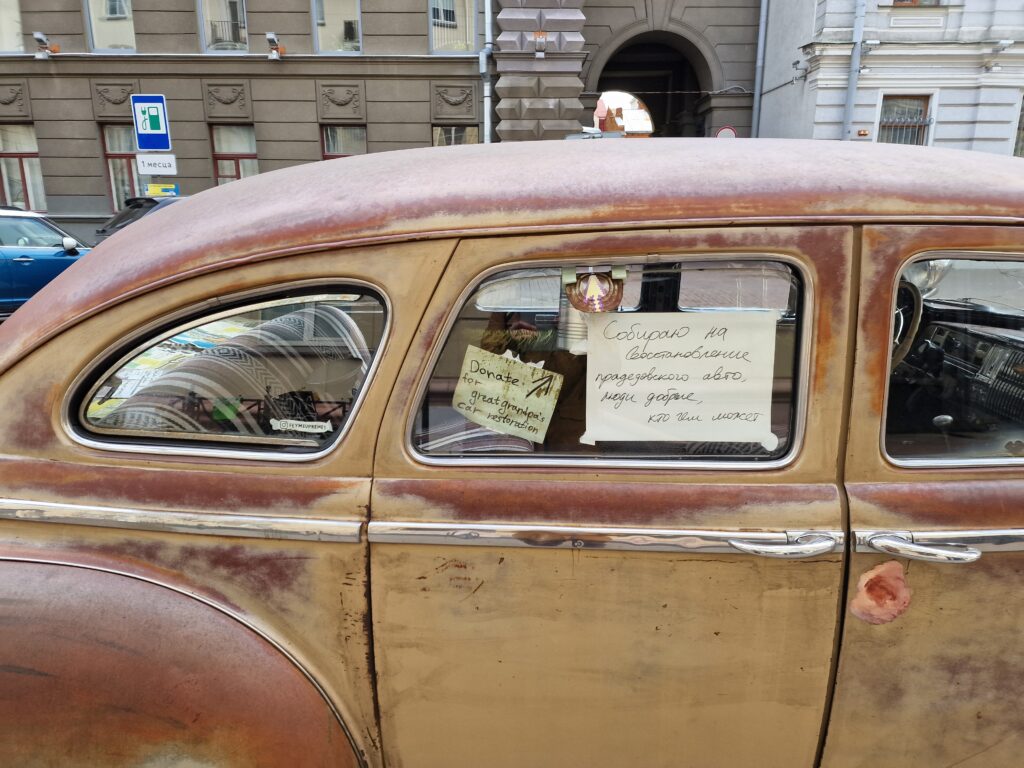

I don’t make this claim lightly, but spending a day in Belarus will expose you to more remnants of its Soviet past than weeks spent in Russia—or in any other former Soviet republic, for that matter. While other countries have moved on, Belarusian leaders—well, one leader, to be precise—have purposefully decided to preserve as many of the old Soviet symbols as possible. After wandering through a couple of grand, chandelier-filled shopping malls and visiting the impressive Holy Spirit Cathedral, I stumbled upon a small outdoor market which had some of the trappings of a traditional Christmas market but with a few noticeable exceptions: mulled wine and cheer. What truly caught the eye, however, were the enormous samovars on display, their polished surfaces gleaming as steam rose from them, ready to serve piping hot tea—a timeless Belarusian pursuit.

My wanderings eventually took me to the vast expanse of Independence Square, one of the largest in Europe, where I found myself dwarfed by its vastness. On one side, the Church of Saints Simon and Helena stood quietly, its simple red brick walls a gentle contrast to the imposing statue of Lenin across the square, looming in front of the most impressive government building this side of Transnistria. It wasn’t until after I left Belarus that I learned this very square had been the site of courageous protests in the summer of 2020, with citizens demanding Lukashenko’s resignation. On my way back to the station, I found myself standing before the Minsk Gates, their towering presence a striking monument to the Soviet era, offering a fitting conclusion to my exploration of a city where the echoes of history were ever-present.

The return journey was far from uneventful. After a five-hour wait in the bus queue and a surprisingly thorough round of questioning, the driver, for reasons unknown, performed a heart-stopping U-turn just shy of the Lithuanian border and headed back to the Belarusian immigration office. As a guard with a towering high-brimmed hat boarded and muttered in Russian while pacing the aisle, the entire bus was on edge. Eventually, he wandered off, and I was stamped back into the EU, continuing my journey to Vilnius. Trying to encapsulate all the moments and impressions of the trip into an 800-word post is an impossible task, but I can say with certainty that the experience surpassed my expectations. The city may not boast the iconic landmarks of Paris or Barcelona, but wandering through it felt like stepping into a living museum, as though I had been transported back to the USSR in 1990. The atmosphere was thick with history, and the feeling of being immersed in a time capsule made the visit well worth it. Still, a change in leadership would likely be needed before I’d consider returning—though that’s a small price to pay for such a fascinating, if unusual, glimpse into the past.

J